Broadened spans of control often lead to conflicts

One popular restructuring measure in companies is to broaden the span of control and increase the number of employees reporting to each manager. For one, this saves on money, since a manager now covers more direct reports. Secondly, it reduces complexity for the higher levels of management, since they now have to speak to fewer managers. What unburdens the higher levels, however, places an additional burden on the lower levels of management, because they have to manage the work and development of more employees.

In this situation, many companies consider implementing elements of self-organisation. This way, they hope to reduce the pressure caused by the broadened span of control, since employees take on more responsibility and fewer reportings are necessary. The move also corresponds to the trend of flattening hierarchies.

But what appears as logical and sensible at first, in practice often comes with surprising hurdles and challenges. Many companies experience that new frictions emerge between differently managed parts of the company, since self-organisation and functional hierarchies follow different logics, which – to the extent that the participants are not explicitly aware of them – collide.

What happens at this point?

A broadened span of control is a classic instrument of functional hierarchies, the main goal of which is to make work more efficient and effective, in this case to get more work done with fewer people. The upper management, however, still has the same expectations of the new level (often middle management), that is, they assume that the now reduced number of managers are still as informed about everything as they were in the past, and can thus report in detail to their superiors.

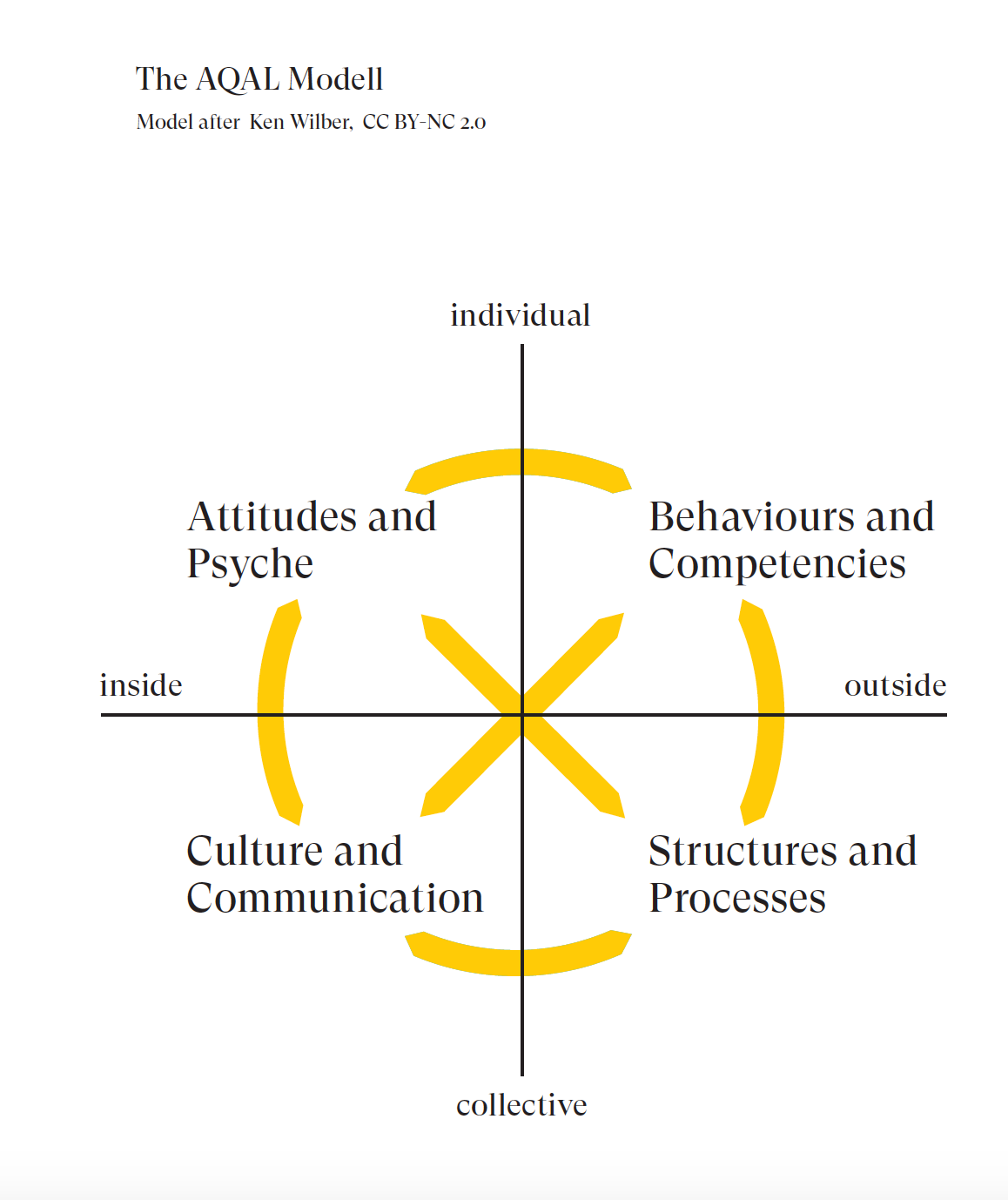

If we take a look at our AQAL, the model that helps us understand change more holistically, then we can see that, through the broadened span of control, the level of processes and structures has changed, all other aspects, however, remain the same. If nothing changes on the other levels, this leads above all to the overload of the now reduced number of direct reports, which can lead to burnout.

If individual teams in companies implement elements of self-organisation and agile project-management, the other three quadrants will inevitably change as well. For it is a central characteristic of self-organisation, that tasks are no longer mandated “from above”, but distributed more self-responsibly throughout the team. Decisions shift from superiors to employees that are seen as especially competent in the particular area. In the course of this transformation, team members become essentially more independent and can also become the primary contact person for outside partners. This means that, in self-organised contexts, there’s no point in asking to speak to the manager, because the competent, self-responsible employee becomes the primary contact person.

…

Above, I started to describe the frequent tensions arising when hierarchically managed companies increase the span of control and introduce elements of self-management as a way to decrease the work burden of lower levels of management. We now have two different ways of leading and organising work operating in one company.

Frequent Misunderstandings …

Within a team, this new distribution of tasks often works quite smoothly. But at the intersections or seams to the rest of the organisation, there will be friction. For the old functional hierarchy will have the same expectations of the self-organised parts of the organisation as before. Superiors assume that the existing management staff will be able to give detailed reports about all important activities within the team. But not only can the manager no longer do this, it is even in contradiction to the principle of self-organisation.

From the perspective of the old management, the self-organised way of working appears inefficient and difficult to control. The new teams seem to elude the control of the top management, which no longer knows who is working on what and how. The self-organised parts in turn feel limited and distrusted through leadership’s need for control, and the employees, who are now taking on much more responsibility, don’t feel valued for their contribution.

From companies, in which these different forms of leadership co-exist, we know the dilemma from both perspectives. The hierarchically organised leadership team is confronted with a contact person that says, for example:

“I can’t give you the concrete details about that. My co-worker X handles that.”

“I can’t make that decision, that’s Y’s area of competency.”

“I can’t accept your proposal directly, but I’ll hand it over to the team.”

No wonder that the leadership on the highest level feels like they are losing their grasp on this lower level. They feel insecure and are afraid of having to bear the legal consequences of mistakes. This can lead to an increased desire to surveill, for example in the form of further reportings. These, however, feel very inefficient for the self-organised team, as the reports serve not to manage work processes, but to surveill them.

Accordingly, the self-organised team feels unwell about this situation. They see their newly won independence (which they are proud of) disregarded, and don’t feel seen in their distributed competency. Team members often complain amongst each other and say:

“They’re expecting things of us that don’t make any sense and are completely inefficient.”

“They don’t see that we’re doing excellent work.”

“Leadership gets the laurel wreath, but it’s we that do all the work.”

… can be resolved

These mutual misunderstandings can, in our experience, only be resolved when both sides come to understand themselves and the other better. Functional hierarchies and self-organisation are expressions of different value systems and basic assumptions about leadership and collaboration, and it’s important to make these mutually transparent. In the scenario sketched out above, the upper management wants to lead the company as efficiently and responsibly as possible. In order to do this, they assume that they have to have as much information as possible, and that important decisions be made by a few key employees.

In the self-organised team, on the other hand, decisions are made where the competencies lie. Processes and structures are considerably more flexible, and restructure themselves according to the situation. For this it’s necessary to communicate openly with each other and to know who has which competencies. Through this process, teams have often developed a larger space of trust with each other.

It’s not easy to manage the intersections between these different forms of organisation. Clearly defined agreements and a mutual understanding of what the other needs to work are a great help here. It’s not enough to intellectually understand the other model. It also has something to do with learning to trust the system emotionally instead of rejecting it intuitively. Self-organised teams can develop an understanding of what hierarchically socialised leadership staff might need to feel oriented, while the latter in turn can learn to appreciate the added value of self-organisation.

*** *** *** ***

If you want to know more about which role new mindsets and inner competencies play for the future of work – and, above all, if you want to concretely try out and realise them – visit our new online course The Future of Work needs Inner Work.

In 36 videos, worksheets and exercises, as well as live online session, you’ll learn how to successfully and sustainably realise the Future of Work and make your company more innovative, effective and authentic.