When companies begin (whether partially or radically) to dissolve fixed structures and introduce agile methods, central management functions, such as strategy development, recruitment and quality control, also change. Instead of the company leadership, much broader parts of the staff or even the entire team are now responsible for making sure that every employee knows on what and how to work. In a series of articles, we want to take a closer look at these individual functions and describe how they change on the path to self-organisation.

We’ll begin with quality control.

Depending on the organisational structure, quality can not only be managed and controlled in many different ways, it can also mean many different things. If we take our bearings from the development model of spiral dynamics, then we can assume that …

- “blue” bureaucratic institutions are especially keen to “do things correctly”. This mainly means that standard procedures are controlled with the help of fixed rules, guidelines and protocols.

- “orange” functional hierarchies, by contrast, attempt to foster personal initiative in employees in order, on the one hand, to continually optimise existing processes, and, on the other hand, to develop new ones. Quality is here often managed through indicators, KPIs, OKRs, balance scorecards, etc.

- The quality designation “green”, for companies focused on community and social responsibility, often applies less to the control of the product in the narrow sense, but includes, above that, the quality of relationships within the team, as well as with stakeholders, suppliers and customers.

- On the next level, which is of particular interest to us with regards to self-organisation, and which is labeled as “teal” by Laloux, as “yellow” in spiral dynamics, the concept of quality is further broadened. These companies take on a systemic perspective that actively considers even the unintended consequences of their activities (how is our product used? what consequences ensue for society and environment?) A product or service is then deemed to be of high quality when it corresponds to the larger mission and vision of the organisation: when it realises the organisations purpose.

How is quality managed in a company?

Companies with flexible organisational structures no longer assume that quality has to be managed and controlled by a specially dedicated department or a few select individuals. Instead, the whole team feels responsible for the work and product meeting the collectively set quality standards. For this to work, employees need a whole new set of competencies, or it can occur that no one really feels responsible at all or even knows which quality standards apply. As a result, quality would inevitably decline.

Here are some of the necessary inner competencies:

Individual Competencies

Employees have to be able to reflect on themselves, by, for example, asking themselves: What do I personally have to be aware of for me to do quality work? Which standards do I have and want to follow? What information do I require? What kind of an environment do I need to be self-motivated and innovative in my work? How strongly am I connected to the mission of the company, in order to put myself in its service?

Relationship Competencies

To keep work processes and results at a high standard, self-organised teams need a series of communicative abilities. Employees need to be able to discuss their own and others’ mistakes, as well as tensions and problems, with colleagues, superiors, or partners. They need to be able to clearly and explicitly share their own requirements and ideas, and agree on binding standards as a team. There needs to be an open and honest dialogue about which competencies are necessary to ensure high quality and allow for the continuous improvement of standards and processes through feedback loops.

At this point it’s interesting to reflect on what managers, who previously did quality control, may need, in order to engage with the new approach and responsibly let go of their control mechanisms.

Field Competencies

While, in hierarchical structures, it’s enough if every employee keeps an eye on “their” part of the work, in self-organised companies they have to be able to keep an overview of the processes in their company as a whole, in order to gage opportunities as well as weak points. They have to be able to understand why a certain result was unsatisfactory. In order to not be overwhelmed by complexity, they need to be able to trust not just their reason, but also their intuition. This competency, knows as meta-reflection or meta-cognition, is key to distributing quality control in a team.

Sounds a little abstract? Here’s an example!

Let’s take a look at a concrete example:

The following answers were given by Franziska Kreische, who has been a member of the betterplace lab since 2014.

In the betterplace lab, the Think and Do Tank that Joana founded in 2010 and that has been self-organised since 2015, quality is a guiding value. There, it’s not so much about “doing things the right way” or optimising standard procedures, but more about staying true to the company’s mission and vision. We make an effort to be as socially effective as possible, that is, we try to research and convey our knowledge in such a way that it has a maximally positive impact on society. Every team member has their own individual quality standards, which may in part deviate from that of their colleagues: while one colleague may place a lot of value on the originality of their research, another may care more about as broad a reception as possible. But aside from these differences, there is a broadly shared understanding of the requirements that our work needs to meet.

Quality Control in projects

The project leaders, as well as anyone else working on a project, are always collectively responsible for the successful execution of a project. They reflect openly and transparently on their work not only amongst themselves, but also with other colleagues that have special competencies not present in the project team. This “consultation process” is completely competency-based and of central importance for the quality of the projects.

In order for team members to be able to give critical and conflict-prone comments and feedbacks to projects, we had to learn how to communicate openly and transparently, for example, according to the principles of nonviolent communication. Teams that are unable to do this won’t dare to address their colleagues about mistakes they’ve made, or will do so in a way that damages the relationships and trust among colleagues. Over the course of the years, we’ve expanded the scope of what we’re able to tell each other, and have thus won much precision and clarity. This has had extremely positive effects on the quality of our work.

Part of quality control is that teams continuously reflect on their standards and requirements. Within the team, we define what requirements we have for which competencies. To these belong such competencies such as team leadership, project conception, project management, Future of Work-competencies, etc. Within each area there are different gradations, and we don’t expect everyone to be equally good at everything. In the extensive feedback talks that we hold with each other once a year, these standards serve as orientation. At the same time they can be useful tools to consider in which areas an individual employee would like to improve.

Apart from that, the team has established some formal requirements for project management. At the start of a project, goals are defined and put in writing together with the clients/project partners. These are, together with pre-defined milestones, presented at the weekly team meeting. At the end of a project there is an obligatory debriefing, at which expectations and goals are compared with the results. Learnings, also critical and “difficult” ones, are shared widely in order to promote knowledge building in the team.

Further formal processes of quality control are a 4-eye-principle during the signing of contracts and bills and the obligatory involvement of the financial overseer during the preparation of offers, and the team overseer during the onboarding of new employees.

Control and further development of organisational processes

Next to individual projects, the team also concerns itself with the quality and further development of organisational processes, such as recruiting and onboarding, project and capacity planning, strategy development and salary negotiations. The respective circles (borrowed from holacracy) are responsible for these processes. We have circles for finances, team, strategy, publicity overview and IT. The circles are comprised of the in each case most competent employees, and in many cases (in the optimisation, adaptation and development of processes) they are thus largely authorised to make decisions for the entire company. Decisions that require the approval of the team are, depending on the dimension, arrived at by means of consensus, consent, or two-thirds majority.

How do we deal with mistakes?

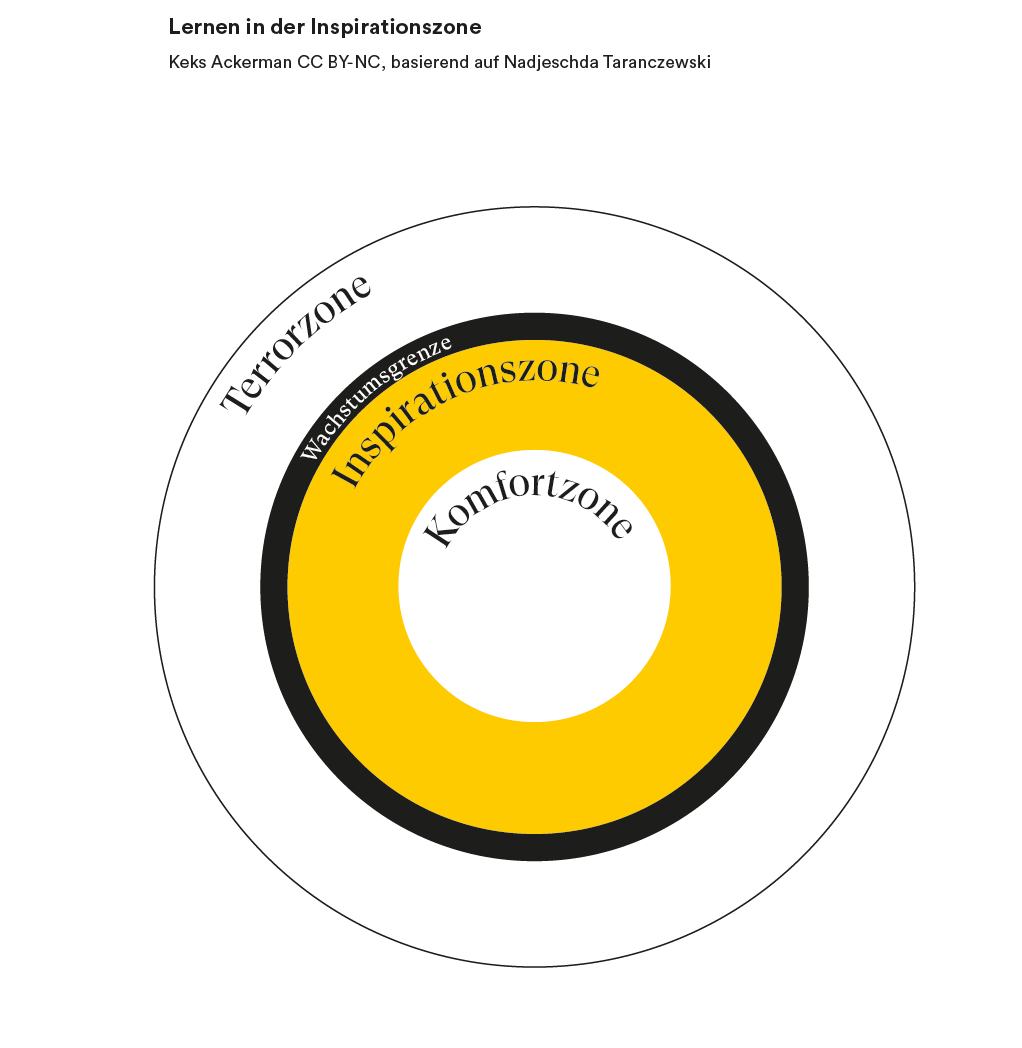

The team assumes that everyone makes mistakes, and that we can only attempt to identify and correct them as early as possible, as well as to share them so openly that everyone can learn from them. In our team we use a learning model, according to which individual employees are either in the comfort zone, the inspiration zone, or the terror zone. We have a shared understanding that only the person who moves outside of the comfort zone can develop something new and be innovative.

This concept helps us not to stigmatise mistakes, but to work on them constructively. In our weekly team meetings there is a special agenda point for sharing one’s difficulties with regards to a project or a partner.

As our team culture is very appreciative and trusting, most mistakes can be easily addressed and solved collectively. In the consulting process, every employee can turn to more competent colleagues, and look for solutions to their problems together.

In the project debriefings, we attempt to find, next to the origins of problems, ways in which we can avoid them in the future. Many of our processes for quality control, like the monthly reports to the financial overseer, or the close collaboration with the team circle about staff issues, have emerged from previous mistakes. We don’t see this as a shortcoming, but as a special quality of our collaboration.

In organisations with agile and fluid structures, quality control is distributed throughout the entire company. As in a swarm, individual employees have an overview of all the company’s activities, and know which standards apply, what their own contribution to these is, and how quality can be further developed. Some aspects of quality control are formalised, others rely on the latent, embodied knowledge of employees. The latter, however, is not just implicit, but can be described by team members and passed on to new employees.

Just as important as distributed responsibility, however, is that the standards of quality change in a company like the betterplace lab. Employees strive for excellence because they want to realise their own potential as well as pursue a shared entrepreneurial goal that will change society for the better. Quality has less something to do with meeting the expectations of others, securing oneself against the complaints of clients, or gaining a competitive advantage, and more with making a coherent and effective contribution to the world.

Joana Breidenbach, Franziska Kreische (betterplace lab)

*** *** *** ***

If you want to know more about which role new mindsets and inner competencies play for the future of work – and, above all, if you want to concretely try out and realise them – visit our new online course The Future of Work needs Inner Work.

In 36 videos, worksheets and exercises, as well as live online session, you’ll learn how to successfully and sustainably realise the Future of Work and make your company more innovative, effective and authentic.